Paperback cover blurb

TRAVEL TO THE BOTTOM OF THE EARTH…

to a place you never dreamed existed.

BENEATH THE ICE…

a hand-picked team of specialists makes its way toward the center of the world. They are not the first to venture into this magnificent subterranean labyrinth. Those they follow did not return.

OVER THE ROCKS… ACROSS THE YAWNING CAVERNS…BEYOND THE BLACK RIVER…

You are not alone.

INTO THE DARKNESS…

where breathtaking wonders await you—and terrors beyond imagining…Revelations that could change the world—things that should never be disturbed…

AT THE BOTTOM OF THE EARTH IS THE BEGINNING.

KEEP MOVING…

toward a miracle that cannot be…toward a mystery older than time.

My thoughts

It takes a lot of nerve to write a lost world story set in the modern day, particularly one that borrows heavily from Journey to the Center of the Earth. But that’s exactly what we have in this techno-thriller.

Subterranean opens when the two main characters, paleoanthropologist Ashley Carter and expert caver Ben Brust, are recruited by the U.S. military to investigate an enormous cavern in Antarctica. There are archaeological ruins inside the cave dating back before humankind had evolved. Who -- or more precisely, what -- built the ruins? The answer lies deeper in the cave system. Carter and Brust will lead an expedition into the depths of the Earth to find out, a journey that a previous team attempted, but never returned.

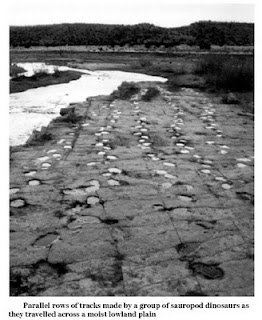

The monsters populating Subterranean are not prehistoric survivors in the strictest since, but the plot and the setting rely heavily on paleontology, so I'm not bending the rules too much. The novel is about finding out what creatures inhabited Antarctica in the 30-million-year gap between the extinction of the dinosaurs and the coming of the ice. Many authors would've used aliens to explain away the pre-human ruins, and I will give Rollins credit for coming up with a more imaginative and more interesting idea.

That said, Subterranean isn't a good book by any stretch of the imagination, with boring characters and frequent action sequences that defy logic. The main villain will offend some readers because of the ethnic stereotyping, and the monsters will feel very familiar to anyone who has seen Jurassic Park. Still, for some reason, I liked it. Why? I'm not quite certain. Perhaps because it is an old-fashioned lost world story with an appropriate sense of mystery and wonder. Or maybe because I read it at a time in my life when I was looking for some popcorn-movie escapism, and it fit the bill.

Subterranean is a good "bad book" -- not one I could recommend if you prefer your literature to be, well, literary, but a fun one as long as you don't take it seriously. Be warned that it does weigh in at a whopping 430 pages, which is about 130 pages more than the author honestly needed to tell the story.

Trivia

- James Rollins is the pen name for veterinarian and amateur spelunker Jim Czajkowski. He has written several thrillers where evolutionary biology and archeology are the main focus.

- The author's web site is www.jamesrollins.com